Computer Memory - 1

Following summarizes my understanding of computer memory from various resources.

NOTE: Many of this summary are full quotes from books; all diagrams are copied from books.

Review

- Main memory is a piece of hardware wherein there’s a one-dimentional array of bytes, each with its own address.

- A program is a binary file containing machine instructions on a harddrive.

- For these machine instructions to be run, they must first be loaded on to memory. That’s because main memory and registers built into the processor (aka CPU) are the only general-purpose storage that the processor can access directly. There are machine instructions that take memory addresses as arguments, but none that take disk addresses.

Requirement of Main Memory Addressing

- A user process must not access operating system’s memory space

- A user process must not arbitrarily access another user process’ memory space

- A process maybe larger than the total available physical memory

- A programmer needs not be aware of how physical memory space for the process spawn by his program is allocated; he only knows his program needs 30KB of memory and that variable X is at address 0 relative to the 30KB (actually, unless he is writing assembly code, he probaly doesn’t even need to know this, but rather the compiler.)

- A programmer prefers to reason about his program in terms of

segment, which abstracts memory addresses.

A user process should not access memory of another or of the operating system.

To solve #2, we separate per-process memory space. And to that end, we need to:

- Determine the range of legal addresses that the process may access

- Ensure the process can access only these legal addresses

One implementation is by using base and limit registers for storing the smallest legal physical memory address and the size of the range. CPU hardware compares every address generated in user mode (by the user program) with the registers. The base and limit registers can be loaded only by the operating system, which uses a special privileged instruction which can be executed only in kernel mode. Since only OS executes in kernel mode, only the OS can load the two registers.

The OS executing in kernel mode has unrestricted access to both OS and users’ memory.

A Process maybe larger than the total available physical memory and the Programmer needs not care about physical memory address

A few notes about different levels of programming languages.

Programmer typically writes software in high-level languages which provides constructs that geared towards human’s readability.

But computers (or more precisely the CPUs) can’t understand that language. It only understands machine code which is the lowest low-level language (the notion of low/high is relative to how far away the code is to machine or human’s understanding; the lower the level, the harder it is for human to understand and the easier for the machine to understand and vice versa).

Developers write software in text files using high-level language. In order for it to be executable by the processor, that text file must be converted to a binary file, which is the assembled version of a compiled program (a program written in assembly language).

Assembly language is specific for each processor architecture (its instruction set, registers…) and contains the lowest-level constructs that are directly supported by the processor - e.g. it lets you move a byte of data from a specific location on memory onto some specific register in the processor. Typically, there’s a one-one correspondence between assembly language and the processor instruction set.

The assembled version translates assembly code line-by-line to appropriate machine language code - e.g. the binary file. So by studying the assembly program, we can understand a good thing about its corresponding binary.

The point we should remember is that an assembly program is a text file that has several sections:

- Data section where initialized data is declared and defined.

- BSS section where uninitialized data is declared.

- Text section where code is placed.

Here’s a yasm program for x86-64 architecture that prints out the number 10. Original snippet from here with modification to illustrate my point.

sample.yasm

section .data

msg dd '10'

nl dd 0x0a

msgLen equ $-msg

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov rax, 1

mov rdi, 1

mov rsi, msg

mov rdx, msgLen

syscall

mov rax, 60

mov rdi, 0

syscall

To run this program, run the following commands but don’t ask me why:

yasm -f elf64 sample.yasm

ld -o sample sample.o

./sample

But what we’re interested is its list file, which is generated with this command:

yasm -g dwarf2 -f elf64 example.asm -l example.lst

(Again, don’t ask me what a list file is, read x86-64 Assembly Language Programming with Ubuntu - 5.2.1 to find out more.)

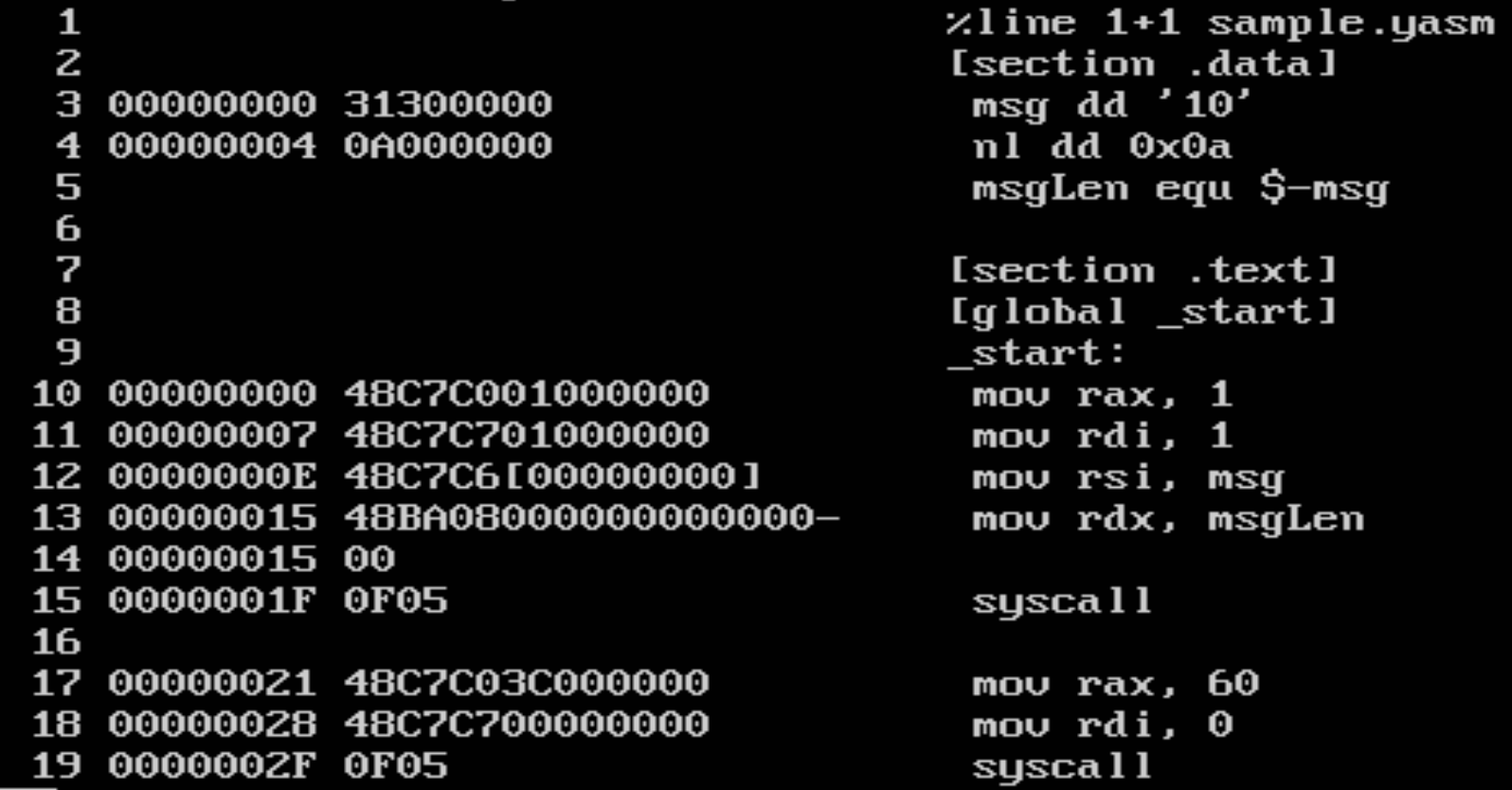

And this is the list file:

This is how to interpret this each line in this file. Following is a line in the data section:

3 00000000 31300000 msg dd '10'

- 3: the line number

- 00000000: relative address in the data area of where the variable will be stored. Since msg is a double-word variable, the next location starts at 0x00000004.

- 31300000: the value 10 in hex as placed in memory

Note example and description shamelessly compies [x86-64 Assembly Language Programming with Ubuntu - 5.2.2].

As one can see, the variables are simply referenced to by its relative memory location (to the program’s memory space). And remember: there are machine instructions that take memory addresses as arguments, but none that take disk addresses.

This means the relative location of a variable/instruction in a program (to the program’s memory space) is non-trivial. If a program’s memory space is 64KB, the programmer expects that he should be able to reference some variable at byte 32.000th.

But what if the physical memory is only 16KB? When the physical memory is smaller than the memory space of a program, we are presented with two problems:

- Since a program (in its binary format) must be loaded on to memory for it to be run, how can a 64KB program be loaded onto a 16KB physical memory device?

- If the programmer access a variable at location greater than the 15.999 th byte, what happens?

The concept of virtual memory vs physical memory and related techniques solves this problem.

It is noticed that even though a program’s memory space maybe larger than available physical memory, at one point in time, only certain parts of the binary is actually run. Therefore, it makes sense to load only those parts into the memory and keep the rest on disk.

When parts of the program is loaded onto memory, the OS and supported hardware gives the CPU the illusion that:

The program was never splitted and partly loaded but rather loaded as a whole onto an imaginary physical memory device that adequately contains all of the program’s memory space.

This technique solves the two issues and is called Dynamic Loading and relies on the concept of virtual/physical memory (the hardware book calls this Overlay, maybe there are subtle differences).

Note: With this enhancement, the size of a binary file is not limited by the physical memory size anymore, however it’s still limited by the range of addresses that the CPU can read - e.g. at the simplest form, the physical number of address lines provided by the processor. More at Computer Architecture and Organization - 5.2.4 and 8.6.2.

Let’s discuss more about this grand illusion of virtual and physical memory:

- Virtual Memory: address generated by the CPU - the CPU reads the program in binary format and generates memory address at which to fetch data according to the program’s description.

- Physical Memory: address received by the memory hardware (to instruct it to return data from that physical address)

In other words:

The set of all logical addresses generated by a program is a logical address space. The set of all physical addresses corresponding to these logical addresses is a physical address space.

The address generated by the CPU and the address received by the memory hardware are different and the CPU never knew the physical memory received a modified memory address instead of what the CPU sent out.

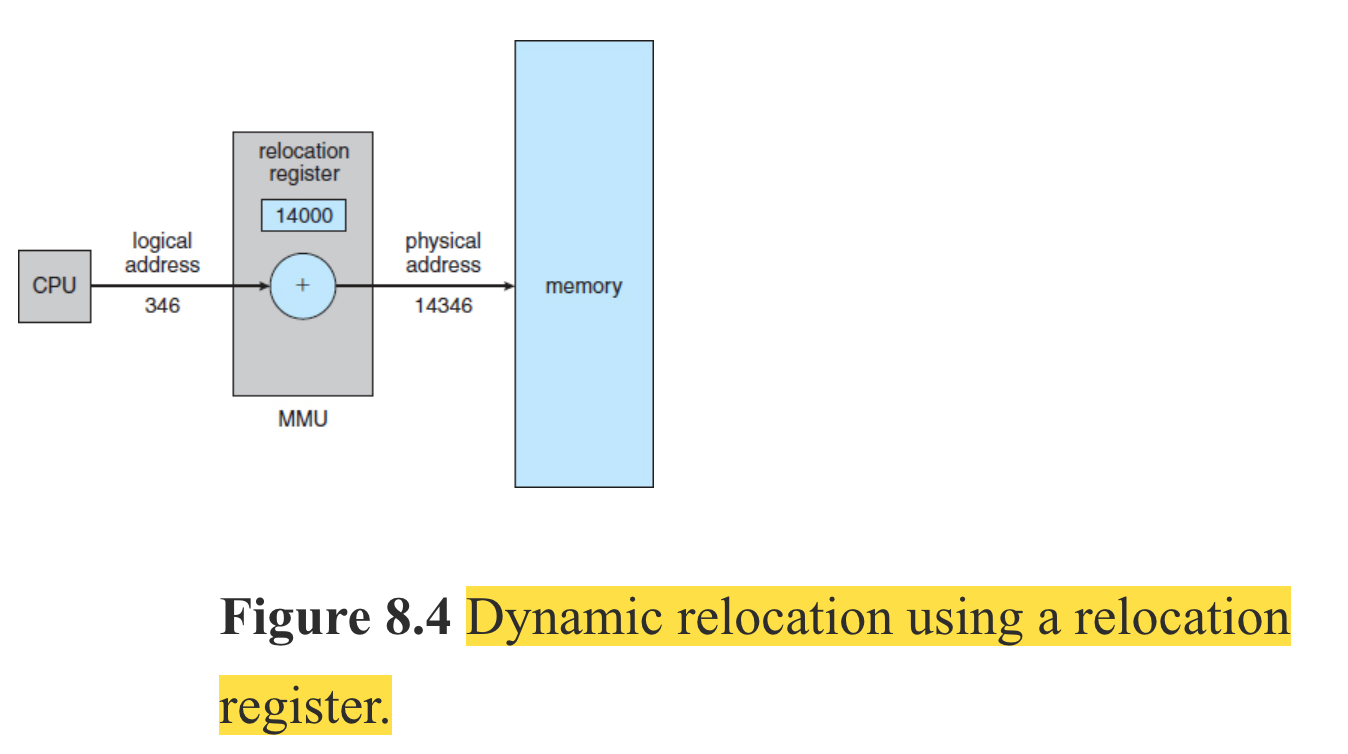

Who modified memory address sent from CPU to physical memory device you ask? It’s the memory management unit (MMU). It maps from virtual memory address to physical memory address at runtime.

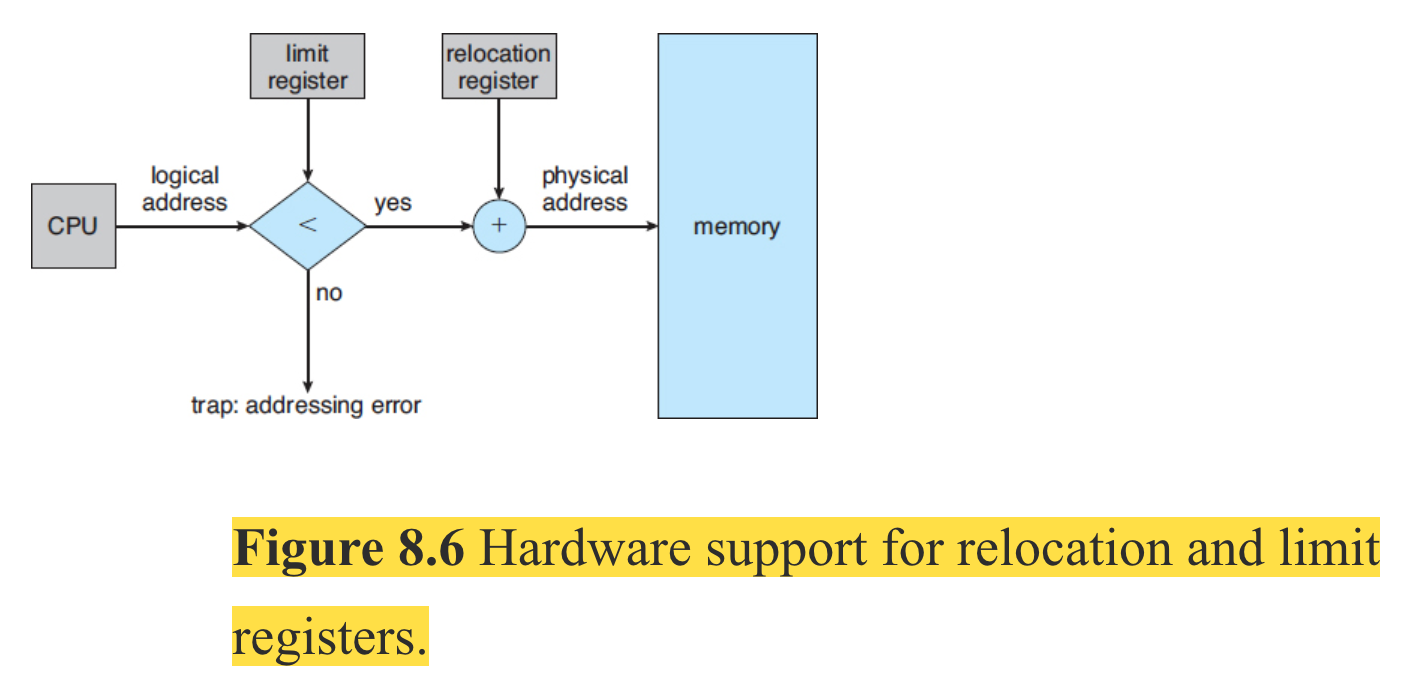

Remember our discussion on how hardware supports prevention memory protection between user processes and between a user process and an operating process by using a base register and limit register?

To create the virtual/physical memory illusion, the MMU replaces the base register with relocation register which handles the translation from virtual address to physical address (the limit register is still kept but not shown in the picture below).

The relocation register keeps an offset into the physical memory. That offset denotes the start of the virtual memory of a process on the physical memory.

Here’s how the whole thing look like with the limit register.

A Programmer refers to the Process’ Memory Space in terms of Segments

Do programmers think of memory as a linear array of bytes, some containing instructions and others containing data? Most programmers would say “no.” Rather, they prefer to view memory as a collection of variable-sized segments, with no necessary ordering among the segments.

When writing a program, a programmer thinks of it as a main program with a set of methods, procedures, or functions. It may also include various data structures: objects, arrays, stacks, variables, and so on. Each of these modules or data elements is referred to by name.

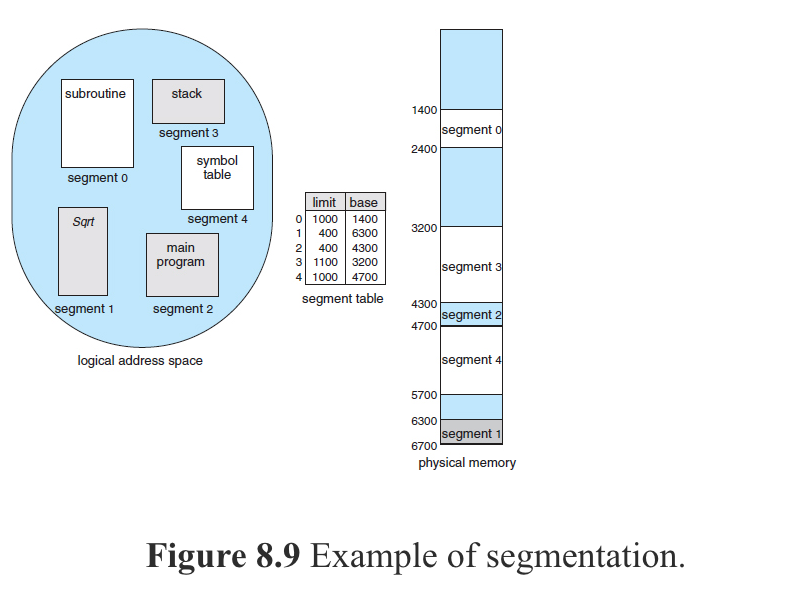

Segmentation is a memory-management scheme that supports this programmer view of memory. A logical address space is a collection of segments.

Each segment has a name and a length. The addresses specify both the segment name and the offset within the segment. The programmer therefore specifies each address by two quantities: a segment name and an offset.

A C compiler might create separate segments for the following:

- The code

- Global variables

- The heap, from which memory is allocated

- The stacks used by each thread

- The standard C library

Hardware supports for segmentation by providing a mechanism called Segment Table which contains a pair of segment base and segment limit (essentially a base and limit register) for each segment.

The book Operating System Concepts 9th Edition, after discussing on Segmentation based on the premise that this technique was born because programmers typically refer to program in terms of segments and that the compiler will create separate segments of a program as shown above, it introduces Paging by:

Segmentation permits the physical address space of a process to be non-contiguous. Paging is another memory-management scheme that offers this advantage. However, paging avoids external… wereas segmentation does not.

This introduction does not sit well with me in terms of logical coherence. Segmentation was introduced as a solution to programmers’ desire to view program in terms of segments (not about non-contiguity of the physical address space of a proces). When I read this part, I didn’t know if paging replaces segment (and if programmers will now refer to their program in terms of paging or if compilers will now produce pages instead of segments). The book did not mention in the text below how these two concepts/techniques connect with each other except for an example of an Intel CPU.

Therefore, I’ll just use my reasonable imagination to say that:

- Segmentation is a concept that was born from programmers and is supported by compilers.

- Segmentation is implemented with hardware support.

- Its implementation suffers external fragmentation.

- Paging is then added after segmentation happens to solve this issue.

Paging also solves the problem of fitting memory chunks of varying sizes onto the backing store (think harddisk).

Paging implementation:

- Physical memory is splitted into fixed-size blocks called Frames

- Backing store is splitted into fixed-size blocks that are one or multiple frames

- Virtual memory is splitted into fixed-size blocks called Pages

- Frame size == Page size

When a process is to be executed, its pages are loaded into any available memory frames from their source (a file system or the backing store).

Memory management in IA-32 systems is divided into two components—segmentation and paging—and works as follows: The CPU generates logical addresses, which are given to the segmentation unit. The segmentation unit produces a linear address for each logical address. The linear address is then given to the paging unit, which in turn generates the physical address in main memory. Thus, the segmentation and paging units form the equivalent of the memory-management unit (MMU).

Note that the segmentation unit here may be implemented differently from description above.

Important Points

- No matter what memory management technique is used, the memory address generated by CPU will always target one single location in the virtual memory space which consists of 1 byte.

- Virtual (Logical) vs Physical Memory and Dynamic Loading were born to allow a process’ memory space to be greater than available physical memory - ex: if the CPU is capable of generating 64-bit address, it can address upto 18 billion GB whearas available physical memory is usually only be a dozen GB.

- Virtual memory is giving the process the illusion that it has all the available memory (all the memory addresses that the CPU can generate) to itself.

- When virtual memory is implemented using paging, each process has a page table that maps that process’ memory location in its virtual memory space to corresponding physical memory location. Technically, if the virtual memory space is 18 billion GB (CPU is capable of generating 64-bit address) and page size if 2 MB, then there should be 18 billion * 1000 (MB) / 2 page table entries in each process’ page table. However, various techniques in page table implementation such as multi-level page table reduces that number (and hence memory needed for the page table in a process’ physical memory space).

- Thanks to dynamic loading and other techniques, many virtual memory locations in different processes may actually share the same physical memory location - ex. shared memory page. Also, those technique enable parts of a program to be loaded into memory only when needed, allowing multiple programs to be loaded into memory at the same time (though maybe only parts of each are loaded). All of these in turns contribute to better memoryspace utilization.

- The logical memory space that the CPU can address may be increased through Page Address Extension which allows a 32-bit processor to access a physical address space larger than 4GB. This feature requires OS support and is available on Intel 32-bit architectures.