Kernel - 2

Another week in the mystic land, the land of true freedom has passed. I’m deep in my expedition…

This time, I probably won’t be putting up a new entry, not because there was nothing of note but rather because there were so many extraordinary phenomenons, one leads to another. I’ve taken countless notes along the way but it’s hard to understand these events fully and organize them in a meaningful manner in a journal’s chapter.

Therefore, I’ll just capture my note and put it up here. Will go back to these and organize properly once I’ve grasped the whole chain of these occurrences and a good resting place.

Journal Note #1

General Idea:

Linux kernel development gives execellent introduction to CFS idea:

-

Suppose we have an editor (E) and a video encoder (V) running

- E spends most of its time waiting for input so it’s I/O bound; whereas V is CPU bound since it spends most time applying video coded to the raw data.

- From user’s perspective, E’s latency is important - e.g. we expect to see a letter appeared instantly as we type it, not seconds later; while V’s latency is not concerned - e.g. we don’t care if V finished encoding a video 20 minutes from now or 30 minutes.

- So, CPU’s need for these E and V are different:

- How often a task should be run: E mostly sleeps, waiting for an I/O event therefore it doesn’t need to be scheduled to run as often as V, which constantly needs the CPU.

- How long should a task run once it is run: E sleeps while waiting for user to press a key so it doesn’t have to be run as often. But when a user does press a key, E has to run immediately and probably for a long amount of time before it goes back to sleep (a user types 3, 4 letters at once then stops several seconds).

- Older OS solve this problem by the concept of priority and timeslice:

- Assigning priority and timeslice to each task

- Tasks with higher priority are selected to run more often and usually receive a higher timeslice

- Issues with this paradigm:

- Linux Kernel Development again does wonderful job of giving 4 problems with said paradigm, of which I found the first one to be the most serious:

- With this paradigm, we need a mapping from priority - timeslice and the problem with that is displayed in the example below:

- Ex: priority is expressed as nice value from 0 - 19 and timeslice is 5 time units - 100 time units. That makes nice value of 0 map to a timeslice of 100 and the nice value 19 a timeslice of 5 time units. (Note I used “time unit” instead of an absolute unit because this is an addressable option that the book also mentioned)

- Suppose we have 2 V processes. Since they are not latency-constrained - that is it doesn’t matter if they finish their work immediately or later, they are given a low priority (aka high nice value).

- Let’s assume they are both assigned the nice value of 19. They will each receive a timeslice of 5 time units.

- This means in 200 time units, these two processes will switch back and forth 200/5 - 1 = 39 times (selecting the first process to run is not considered “switch”)

- Assuming switching (context switch) takes 1 time unit each, in 200 time units, the CPU will waste 1 * 39 = 39 time units on context switch.

- Note that if they had been alloted 100 time units each, then in 200 time units, the CPU would have wasted only 1 time unit!

- Now suppose we have 2 E processes. Since they are latency-constrained - that is they need to finish their tasks quickly, they are assigned high priority - aka low nice value (so they can preempt Vs if any)

- Assume 2 E processes are assigned the same low nice value of 0, they will each receive a timeslice of 100 time units.

- This means after its timeslice has expired, an E process has to wait 100 timeunits before it’s run again.

- Imagine a user constantly switching between the 2 E processes, if he somehow manages to switch more than once every 100 time units, then he will experience the unresponsiveness.

- This paradigm is really backward from ideal given that low-priority processes tend to be background, CPU-intensive ones (and therefore should not be switching between themselves so much) and those high-priority ones are user tasks (which should have been able to switch between themselves more often).

- With this paradigm, we need a mapping from priority - timeslice and the problem with that is displayed in the example below:

- Another issue is with process waking up from I/O event:

- Such process is usually I/O bound. They don’t require to be run often but when they do need to be run, they need to be run immediately, preempting anything that’s using CPU.

- With the priority and timeslice paradigm, one may want to give the just-awoken process a priority boost so it can preempt other tasks immediately.

- This idea improves interactive performance but runs into trouble with certain sleep/wake up uses cases where a process can make CPU grant it an unfair amount of CPU time. I imagine this could be a process that constantly sleeps/wakes at certain rate which makes CPU continously raise its priority and therefore gains itself a huge amount of CPU time.

- The belie problem: this paradigm employs constant rate switching but variable fairness.

- Linux Kernel Development again does wonderful job of giving 4 problems with said paradigm, of which I found the first one to be the most serious:

- CFS:

-

Idea is simple: models an “ideal, precise multi-tasking CPU” on real hardware.

80% of CFS’s design can be summed up in a single sentence: CFS basically models an “ideal, precise multi-tasking CPU” on real hardware.

“Ideal multi-tasking CPU” is a (non-existent :-)) CPU that has 100% physical power and which can run each task at precise equal speed, in parallel, each at 1/nr_running speed. For example: if there are 2 tasks running, then it runs each at 50% physical power — i.e., actually in parallel.

On real hardware, we can run only a single task at once, so we have to introduce the concept of “virtual runtime.” The virtual runtime of a task specifies when its next timeslice would start execution on the ideal multi-tasking CPU described above. In practice, the virtual runtime of a task is its actual runtime normalized to the total number of running tasks.

-

A bit more explanation:

- CFS scheduler does not directly assign timeslices to processes but assigns processes a proportion of the processor. Therefore, the amount of processor time that a process receives is a function of the load of the system. This assigned proportion is further affected by each process’s nice value. The nice value acts as a weight, changing the proportion of the processor time each process receives

- It does this by:

- Accounts the time each process has been waiting to run and the amount of time it has run

- Always selects the one that has run the least amount of time to run next

- Note that a there’s no direct mapping between a priority and a fixed timeslice.

- Instead, a process is assigned a “variable timeslice”, which is a function of the total number of runnable processes, which is further affected by the priority.

- The process may run until its alloted time expires, in which case it yields itself or may be preempted when 1) it is time to select the next process to run and 2) there exists a process that has run a smaller amount of time

- When is the time for the selection to happen? It could be when the kernel has returned from handling an interrupt, when a new process has become runnable and is then added to the run queue…

- If a process blocks on I/O, it is put in a sleeping state, is removed from the run queue and therefore, is not considered when the selection happens.

- This effectively means: CFS uses constant fairness but variable switching rate.

- How does CFS solve the problem with

- Scheduling between E and V

- Because E mostly sleeps, its CPU run time is very small while V’s very large.

- As such, whenever a user presses a key, which:

- Wakes the sleeping process and puts it back into the run queue (remember, sleeping processes are not in the run queue)

- Triggers the process of selecting the next task to run

- Then the selection will choose E naturally because it has run the least amount of time.

- In the same manner, since E hasn’t been running at all, in the event that a selection of which process to be run occurs again for whatever reason, E would still be chosen because it still has used far less CPU time than V.

- Scheduling between V and V

- Because the nice priority now does not directly translate to a literal timeslice but is a weight of CPU time a process should have, the proportion of processor time that a process receives is determined only by the relative difference in niceness between it and other runnable processes’

- And also the timeslice is now a function of the number of runnable tasks

- Assume again that the two V have the same low priority.

- Since the “timeslice” now also takes into consideration of the total number of runnable processes (which is two in this case), the scheduler can allocate a better “timeslice” for each which results in lower number of context switches.

- (I don’t even know the exact function but the important point is 1) the scheduler is free from the priority - absolute timeslice mapping and 2) takes into account the number of total number of runnable processes when it calculate the timeslice for a process. It’s reasonable to assume that with such capability, it can come up with a more meaningful timeslice.)

- Scheduling between E and E

- Suppose E1 is using CPU and E2 is sleeping, E1 is in the runqueue whereas E2 is not. Also, since E1 is using CPU, E1 is most likely to be using more CPU time than E2.

- When the user switch to E2, an interrupt happens which:

- Wakes up E2, effectively puts it in the run queue

- Trigger the selection process

- Since E2 has been sleeping, it has used less CPU time then E1, E2 is naturally chosen to be run immediately.

- Scheduling between E and V

-

Process scheduling:

- There are several scheduler classes, each is assigned a priority

- Different scheduler classes implement different scheduling policy such as CFS, real-time…

- Each CPU is attached a run queue which “contains” a number of tasks that are ready to be run aka runnable.

- When it’s time for a CPU to pick what to run next: the run queue is iterated through to find the runnable task that has the smallest vruntime in the highest-priority scheduler

- Below 2 notes might be wrong, need to look at the Scrolls again

- task_struct stores sched info in struct sched_info se # This might be wrong

- sched_info has vruntime # vruntime is in sched_entity, it seems sched_info is for debugging purpose

- task_struct stores sched info in struct sched_entity se -> this is actually what is referred to as “schedulable entity”

- sched_entity has vruntime

There are 2 schedulers in use:

- Main scheduler:

*The main scheduler function (schedule) is invoked directly at many points in the kernel

- Purpose:

- to allocate the CPU to a process other than the currently active one.

- After returning from system calls, the kernel also checks whether the reschedule flag TIF_NEED_RESCHED of the current process is set — for example, the flag is set by scheduler_tick as mentioned above. If it is, the kernel invokes schedule. The function then assumes that the currently active task is definitely to be replaced with another task.

- Purpose:

- Periodic scheduler:

- automatically called by the kernel with frequency HZ;

- Purpose:

- managing kernel scheduling-specific statistics relating to the whole system and to the individual processes

- activate the periodic scheduling method of the scheduling class responsible for the current process

- Entrypoint to the Main scheduler

- function schedule() in kernel/sched.c -

- the rest of kernel uses to invoke the process scheduler, deciding which process to run and then run it

- generic with respect to scheduler classes - it finds the highest priority scheduler class with a runnable process and asks it what to run next

- invokes pick_next_task() in kernel/sched.c.

- pick_next_task()

- This function goes through each scheduler class, starting with the higest priority and selects the highest priority process in the highest priority class

- invokes pick_next_task() of each scheduling class

- function schedule() in kernel/sched.c -

CFS:

- CFS uses red-black tree to manage list of runnable processes to efficiently find one with the smallest vruntime CFS picks the next process: __pick_next_entity() in kernel/sched_fair.c. If there are no runnable tasks left, CFS schedules the idle task

- Adding procsses to CFS tree:

- Happens when a process becomes runnable (wakes up) or is first created via fork()

- code: enqueue_entity() - updates runtime and statistics then invokes __enqueue_entity() to actually insert the entry into the tree

- Removing processes from CFS tree:

- Happens when a process blocks (becomes unrunnable) or terminates (ceases to exist) code: dequeue_entity - updates statistics and invokes __dequeue_entity() to actually remove the process from the tree

Code Flow:

pick_next_task(): for class in descending_priority_scheduling_classes: p = class.pick_next_task() if (p): return p

- Process sleeping and waking up:

- Process sleeps for various reasons but always when it is waiting for an event

- states: TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE (wake up prematurely and respond to a signal if one is issued) and TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE (ignores signal)

- Behavior:

- Task marks itself as sleeping

- put itself on a wait queue

- remove itself from the red-black tree of runnable

- calls schedule() to select a new process to execute

- Waking up behavior: reverse but not sure who initiates all of these

- the event that the process waits on triggers wake_up() on the queue that holds the processes waiting for the data`

- wake_up() wakes up all tasks waiting on the given wait queue and calls try_to_wake_up()

- try_to_wake_up() sets the tasks’s state to TASK_RUNNING, calls enqueue_task() to add task to red-black tree and sets need_resched if awakened task’s priority is higher than priority of current task

- Wait Queue:

- List of processes waiting for an event to occur

- awakens procsses when the condition for which it is waiting occurs. Code elsewhere will call wake_up() on the queue when the event actually does occur

- code: wake_queue_head_t

- code flow:

- task creates a wait queue entry via the macro DEFINE_WAIT()

- task adds itself to wait queue via add_wait_queue

- calls prepare_to_wait() to change process state to TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE/TASK_UNINTERRUPTIBLE

- if state is set to TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE, a signal can wake the process up so check and handle signals

- when task is awaken, checks whether condition is true and exits if it is; otherwise call schedule() again and repeats

- if condition is true, task sets itself to TASK_RUNNING and removes itself from the wait_queue via finish_wait()

- real code: ```C /* q is the wait queue we wish to sleep on */ DEFINE_WAIT(wait);

add_wait_queue(q, &wait); while (!condition) { /* condition is the event that we are waiting for / prepare_to_wait(&q, &wait, TASK_INTERRUPTIBLE); if (signal_pending(current)) / handle signal */ schedule(); } finish_wait(&q, &wait); ```

- Object Representation

struct struct_task {

struct sched_class *sched_class

struct sched_entity se

}

struct sched_entity {

//vruntime info

}

struct sched_class {

//this task will be "extended" to provide schedule-class-specific

//methods to handle enqueue, dequeue and pick next task

}

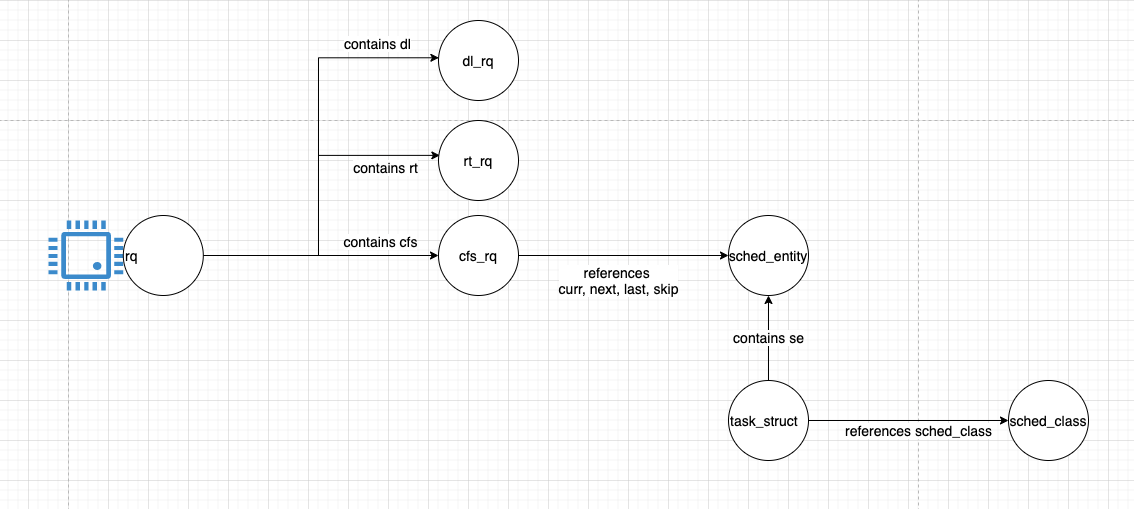

struct rq {

struct cfs_rq cfs

struct rt_rq rt

struct dl_rq dl

}

struct cfs_rq {

struct sched_entity *curr, *next, *last, *skip

}

- A map I’ve drawn myself

- Note on kernel C code:

ifdef:- Often time, kernel code includes blocks of

#ifdef-#endiflike this A Major Guild’s Scrollstruct rq { #omitted #ifdef CONFIG_FAIR_GROUP_SCHED /* list of leaf cfs_rq on this cpu: */ struct list_head leaf_cfs_rq_list; #endif /* CONFIG_FAIR_GROUP_SCHED */ #omitted };This means the block of code inside

#ifdefand#endifis only included in the code ifCONFIG_FAIR_GROUP_SCHEDis defined. Typically, this mechanism is used to turn on and off certain features of the kernel depending on values passed to the compiler at when the kernel is compiled.

- Often time, kernel code includes blocks of

- “What file can be included in a kernel module”:

- Only those under

includedirectories can be included in a kernel module - The path to put in the

#include<path>is always one-level-before/the-file-itself. Ex:/arch/alpha/include/asm/a.out.his included with `#include<asm/a.out.h> - Ref - My question on the Adventurer Camp’s Tavern

- Only those under

- Useful scrolls I have found from other adventurers: